Daxin: Stealthy Backdoor Designed for Attacks Against Hardened Networks

Espionage tool is the most advanced piece of malware Symantec researchers have seen from China-linked actors.

New research by the Symantec Threat Hunter team, part of Broadcom Software, has uncovered a highly sophisticated piece of malware being used by China-linked threat actors, exhibiting technical complexity previously unseen by such actors. The malware appears to be used in a long-running espionage campaign against select governments and other critical infrastructure targets.

There is strong evidence to suggest the malware, Backdoor.Daxin, which allows the attacker to perform various communications and data-gathering operations on the infected computer, has been used as recently as November 2021 by attackers linked to China. Most of the targets appear to be organizations and governments of strategic interest to China. In addition, other tools associated with Chinese espionage actors were found on some of the same computers where Daxin was deployed.

Daxin is without doubt the most advanced piece of malware Symantec researchers have seen used by a China-linked actor. Considering its capabilities and the nature of its deployed attacks, Daxin appears to be optimized for use against hardened targets, allowing the attackers to burrow deep into a target’s network and exfiltrate data without raising suspicions.

Through Broadcom’s membership in the Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative (JCDC), Symantec researchers worked with the Cyber Security and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) to engage with multiple foreign governments targeted with Daxin and assisted in detection and remediation.

This is the first in a series of blogs. This blog provides an overview of Daxin’s capabilities and will be followed with additional blogs providing further in-depth analysis.

Daxin technical overview

As described in more detail below, Daxin comes in the form of a Windows kernel driver, a relatively rare format for malware nowadays. It implements advanced communications functionality, which both provides a high degree of stealth and permits the attackers to communicate with infected computers on highly secured networks, where direct internet connectivity is not available. These features are reminiscent of Regin, an advanced espionage tool discovered by Symantec in 2014 that others have linked to Western intelligence services.

Daxin’s capabilities suggest the attackers invested significant effort into developing communication techniques that can blend in unseen with normal network traffic on the target’s network. Specifically, the malware avoids starting its own network services. Instead, it can abuse any legitimate services already running on the infected computers.

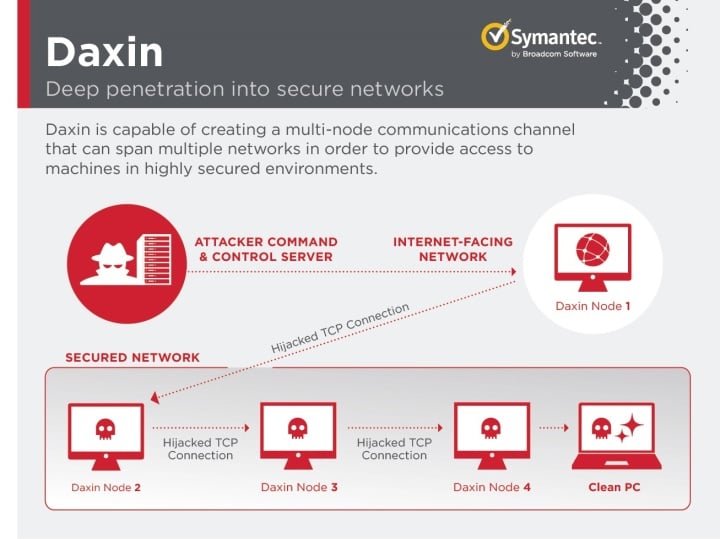

Daxin is also capable of relaying its communications across a network of infected computers within the attacked organization. The attackers can select an arbitrary path across infected computers and send a single command that instructs these computers to establish requested connectivity. This use case has been optimized by Daxin’s designers.

Daxin also features network tunneling, allowing attackers to communicate with legitimate services on the victim’s network that can be reached from any infected computer.

Daxin in detail

Daxin is a backdoor that allows the attacker to perform various operations on the infected computer such as reading and writing arbitrary files. The attacker can also start arbitrary processes and interact with them. While the set of operations recognized by Daxin is quite narrow, its real value to attackers lies in its stealth and communications capabilities.

Daxin is capable of communicating by hijacking legitimate TCP/IP connections. In order to do so, it monitors all incoming TCP traffic for certain patterns. Whenever any of these patterns are detected, Daxin disconnects the legitimate recipient and takes over the connection. It then performs a custom key exchange with the remote peer, where two sides follow complementary steps. The malware can be both the initiator and the target of a key exchange. A successful key exchange opens an encrypted communication channel for receiving commands and sending responses. Daxin’s use of hijacked TCP connections affords a high degree of stealth to its communications and helps to establish connectivity on networks with strict firewall rules. It may also lower the risk of discovery by SOC analysts monitoring for network anomalies.

Daxin’s built-in functionality can be augmented by deploying additional components on the infected computer. Daxin provides a dedicated communication mechanism for such components by implementing a device named “\\.\Tcp4”. The malicious components can open this device to register themselves for communication. Each of the components can associate a 32-bit service identifier with the opened \\.\Tcp4 handle. The remote attacker is then able to communicate with selected components by specifying a matching service identified when sending messages of a certain type. The driver also includes a mechanism to send back any responses.

There are also dedicated messages that encapsulate raw network packets to be transmitted via the local network adapter. Daxin then tracks network flows, such that any response packets are captured and forwarded to the remote attacker. This allows the attacker to establish communication with legitimate services that are reachable from the infected machine on the target’s network, where the remote attacker uses network tunnels to interact with internal servers of interest.

Perhaps the most interesting functionality is the ability to create a new communications channel across multiple infected computers, where the list of nodes is provided by the attacker in a single command. For each node, the message includes all the details required to establish communication, specifically the node IP address, its TCP port number, and the credentials to use during custom key exchange. When Daxin receives this message, it picks the next node from the list. Then it uses its own TCP/IP stack to connect to the TCP server listed in the selected entry. Once connected, Daxin starts the initiator side protocol. If the peer computer is infected with Daxin, this results in opening a new encrypted communication channel. An updated copy of the original message is then sent over this new channel, where the position of the next node to use is incremented. The process then repeats for the remaining nodes on the list.

While it is not uncommon for attackers’ communications to make multiple hops across networks in order to get around firewalls and generally avoid raising suspicions, this is usually done step-by-step, such that each hop requires a separate action. However, in the case of Daxin, this process is a single operation, suggesting the malware is designed for attacks on well-guarded networks, where attackers may need to periodically reconnect into compromised computers.

Timeline

The Symantec Threat Hunter team has identified Daxin deployments in government organizations as well as entities in the telecommunications, transportation, and manufacturing sectors. Several of these victims were identified with the assistance of the PwC Threat Intelligence team.

While the most recent known attacks involving Daxin occurred in November 2021, the earliest known sample of the malware dates from 2013 and included all of the advanced features seen in the most recent variants, with a large part of the codebase having already been fully developed. This suggests that the attackers were already well established by 2013, with Daxin features reflecting their expertise at that time.

We believe that before commencing development of Daxin, the attackers were already experimenting for some time with the techniques that become part of Daxin. An older piece of malware – Backdoor.Zala (aka Exforel) – contained a number of common features but did not have many of Daxin’s advanced capabilities. Daxin appears to build on Zala’s networking techniques, reusing a significant amount of distinctive code and even sharing certain magic constants. This is in addition to a certain public library used to perform hooking that is also common between some variants of Daxin and Zala. The extensive sharing indicates that Daxin designers at least had access to Zala’s codebase. We believe that both malware families were used by the same actor, which became active no later than 2009.

Links to known espionage actors

There are several examples of attacks where tools known to be associated with Chinese espionage actors have been observed along with what we believe to be variants of Daxin.

In a November 2019 attack against an information technology company, the attackers used a single PsExec session to first attempt to deploy Daxin before then resorting to Trojan.Owprox. Owprox is associated with the China-linked Slug (aka Owlproxy).

In May 2020, malicious activity involving both Backdoor.Daxin and Trojan.Owprox occurred on a single computer belonging to another organizations, a technology company.

In a July 2020 attack against a military target, the attackers made two unsuccessful attempts to deploy a suspicious driver. When these attempts failed, the attackers resorted to different malware instead, a variant of Trojan.Emulov. Symantec did not obtain either of the two suspicious drivers used in this attack. However, very strong similarities between this attack and earlier activity in which Daxin was used suggests that it is highly likely the attackers attempted to deploy Daxin before falling back on the other malware.

Developing analysis

In summary, Daxin includes some of the most complex features we have seen in a highly probable China-linked malware campaign. We will publish follow-up blogs over the coming days with more detailed technical analysis and other insights from our research and collaborations.

Protection/Mitigation

For the latest protection updates, please visit the Symantec Protection Bulletin.

Indicators of Compromise

Malware related to Daxin activity:

81c7bb39100d358f8286da5e9aa838606c98dfcc263e9a82ed91cd438cb130d1 Backdoor.Daxin (32-bit core)

06a0ec9a316eb89cb041b1907918e3ad3b03842ec65f004f6fa74d57955573a4 Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

0f82947b2429063734c46c34fb03b4fa31050e49c27af15283d335ea22fe0555 Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

3e7724cb963ad5872af9cfb93d01abf7cd9b07f47773360ad0501592848992f4 Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

447c3c5ac9679be0a85b3df46ec5ee924f4fbd8d53093125fd21de0bff1d2aad Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

49c827cf48efb122a9d6fd87b426482b7496ccd4a2dbca31ebbf6b2b80c98530 Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

5bc3994612624da168750455b363f2964e1861dba4f1c305df01b970ac02a7ae Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

5c1585b1a1c956c7755429544f3596515dfdf928373620c51b0606a520c6245a Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

6908ebf52eb19c6719a0b508d1e2128f198d10441551cbfb9f4031d382f5229f Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

7867ba973234b99875a9f5138a074798b8d5c65290e365e09981cceb06385c54 Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

7a08d1417ca056da3a656f0b7c9cf6cd863f9b1005996d083a0fc38d292b52e9 Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

8d9a2363b757d3f127b9c6ed8f7b8b018e652369bc070aa3500b3a978feaa6ce Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

b0eb4d999e4e0e7c2e33ff081e847c87b49940eb24a9e0794c6aa9516832c427 Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

b9dad0131c51e2645e761b74a71ebad2bf175645fa9f42a4ab0e6921b83306e3 Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

cf00e7cc04af3f7c95f2b35a6f3432bef990238e1fa6f312faf64a50d495630a Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

e7af7bcb86bd6bab1835f610671c3921441965a839673ac34444cf0ce7b2164e Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

ea3d773438c04274545d26cc19a33f9f1dbbff2a518e4302addc1279f9950cef Backdoor.Daxin (64-bit core)

08dc602721c17d58a4bc0c74f64a7920086f776965e7866f68d1676eb5e7951f Backdoor.Daxin (dropper)

53d23faf8da5791578c2f5e236e79969289a7bba04eee2db25f9791b33209631 Backdoor.Daxin (dropper)

7a7e8df7173387aec593e4fe2b45520ea3156c5f810d2bb1b2784efd1c922376 Backdoor.Zala (32-bit core)

8dafe5f3d0527b66f6857559e3c81872699003e0f2ffda9202a1b5e29db2002e Backdoor.Zala (32-bit core)

96bf3ee7c6673b69c6aa173bb44e21fa636b1c2c73f4356a7599c121284a51cc Backdoor.Trojan (32-bit core)

9c2f3e9811f7d0c7463eaa1ee6f39c23f902f3797b80891590b43bbe0fdf0e51 Backdoor.Trojan (32-bit core)

c0d88db11d0f529754d290ed5f4c34b4dba8c4f2e5c4148866daabeab0d25f9c Backdoor.Trojan (32-bit core)

e6a7b0bc01a627a7d0ffb07faddb3a4dd96b6f5208ac26107bdaeb3ab1ec8217 Backdoor.Trojan (32-bit core)

File names attributed to Daxin activity:

"ipfltdrvs.sys"

"ndislan.sys"

"ndislan_win2008_x64.sys"

"ntbios.sys"

"patrol.sys"

"performanceaudit.sys"

"print64.sys"

"printsrv64.sys"

"prv64.sys"

"sqlwriter.sys"

"srt.sys"

"srt64.sys"

"syswant.sys"

"usbmrti.sys"

"vncwantd.sys"

"wantd.sys"

"win2k8.sys"

"wmipd.sys"

"[CSIDL_SYSTEM]\drivers\pagefile.sys"

"[CSIDL_SYSTEM]\spool\drivers\ntds.sys"

Malware observed during overlapping activities:

705be833bd1880924c99ec9cf1bd0fcf9714ae0cec7fd184db051d49824cbbf4 suspected Backdoor.Daxin

c791c007c8c97196c657ac8ba25651e7be607565ae0946742a533af697a61878 suspected Backdoor.Daxin

514d389ce87481fe1fc6549a090acf0da013b897e282ff2ef26f783bd5355a01 Trojan.Emulov (core)

1a5c23a7736b60c14dc50bf9e802db3fcd5b6c93682bc40141d6794ae96138d3 Trojan.Emulov (dropper)

a0ac5f7d41e9801b531f8ca333c31021c5e064f13699dbd72f3dfd429f19bb26 Trojan.Owprox (core)

aa7047a3017190c66568814eb70483bf74c1163fb4ec1c515c1de29df18e26d7 Trojan.Owprox (dropper)

We encourage you to share your thoughts on your favorite social platform.