Breaking SSL Locks: App Developers Behaving Badly

Summary: Symantec analyzed five years’ worth of Android and iOS apps to see how many are sending data securely.

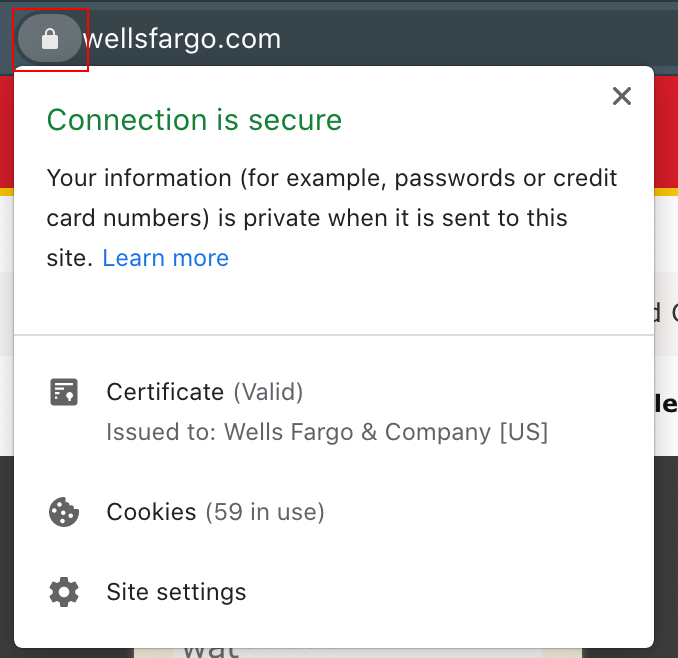

Have you seen that little lock in your web browser that indicates the site you’re visiting is secure? Where is that little lock displayed when you’re using a mobile app?

The padlock icon indicates a secure communication channel between the browser and the server. When the lock is closed and green, the connection is encrypted using HTTPS and an SSL certificate signed by a trusted authority. Your private data, from the browser to the server, is secure. When the lock is broken, the communication channel is broken, insecure, and cannot be trusted. Any data sent to the server is easily visible, can be intercepted, and even compromised by an attacker.

Often mobile apps use the same HTTPS communication channels to back-end services as the web browser. That may make you wonder, where is the little lock being shown? How do you know your private data is being sent securely?

The short answer is you don't, and worse, your data is often not being sent securely - often to the same services you access in your web browser.

We took a look across hundreds of thousands of mobile apps in public app stores and found that those that were breaking the lock were usually doing so intentionally. In addition, users are often none the wiser when it comes to this developer activity.

Highlights:

- In total, 7% of iOS and 3.4% of Android mobile apps intentionally break the lock, actively transferring data to insecure network servers and disabling SSL validation

- Over the past five years, vulnerable iOS apps have not improved, with 2020 containing the highest amount of vulnerable apps (7.6%)

- However, Android apps have been improving year over year, down to 2.4% from close to 5% in 2017

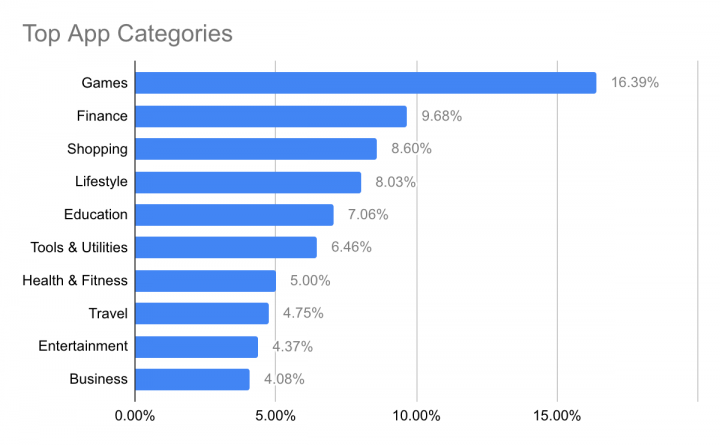

- Vulnerable apps were found across all categories, with "Games" at the top, followed closely by "Financial" apps

- 94% of the vulnerable iOS apps disable Apple's App Transport Security (ATS) restrictions for all network connections

Research methodology

From the millions of mobile apps we've analyzed from public app stores, we focused on the apps released over the past five years from the Apple App Store and Google Play Store. Among the many risky behaviors we currently identify, apps breaking the lock and sending potentially private data via insecure SSL connections that disable validation is one of them. We also looked at the prevalence of app developers disabling the privacy features for apps, including ATS for iOS.

The data set includes iOS apps released on the Apple App Store and Android apps from the Google Play Store from 2017 to 2021.

Trends

The past five years have shown no significant changes with the number of iOS apps breaking the locks. Apart from a slight dip in 2018, the amount has consistently been over 7%.

Android, on the other hand, has shown a positive downtrend over the years. While there were just under 5% of Android apps breaking the locks in 2017, the amount has more than halved and is currently 2.4%.

| Year | iOS | Android | iOS total | Android total | iOS vulnerable | Android vulnerable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 7.29% | 2.40% | 123,260 | 99,170 | 8,980 | 2,376 | |

| 2020 | 7.61% | 2.85% | 593,208 | 776,058 | 45,158 | 22,135 | |

| 2019 | 7.18% | 3.21% | 859,817 | 648,228 | 61,759 | 20,821 | |

| 2018 | 5.67% | 4.51% | 459,041 | 239,460 | 26,050 | 10,809 | |

| 2017 | 7.20% | 4.90% | 393,820 | 249,640 | 28,373 | 12,243 | |

| Total | 7.01% | 3.40% | 2,429,146 | 2,012,556 | 170,320 | 68,384 |

Discoveries

We found that categories of apps transferring data insecurely spanned most categories, with games coming out on top, followed by financial apps. Games are not a surprise, often transferring large amounts of public media content and data. Financial apps, on the other hand, often contain financial data and personally identifiable information (PII), which is a cause for concern.

Threat vectors

As clearly stated by Google:

Many web sites describe a poor alternative solution which is to install a TrustManager that does nothing. If you do this you might as well not be encrypting your communication, because anyone can attack your users at a public Wi-Fi hotspot by using DNS tricks to send your users' traffic through a proxy of their own that pretends to be your server. The attacker can then record passwords and other personal data. This works because the attacker can generate a certificate and—without a TrustManager that actually validates that the certificate comes from a trusted source—your app could be talking to anyone. So don't do this, not even temporarily. You can always make your app trust the issuer of the server's certificate, so just do it.

In addition, an attacker can easily identify all mobile device targets on a network, and choose to intercept the SSL traffic sent to servers they know apps are disabling SSL validation for. There is no longer a need to trick users into installing malicious user certificates and profiles that tend to trigger detection or alert victims that they are actively under a man-in-the-middle (MitM) attack. This can now be done with readily available MitM tools, for example, using the mitmproxy tool:

mitmproxy --mode transparent --listen-port 8080 --ignore-hosts '^(?![0-9\.]+:)(?!([^\.:]+\.)vuln_server:)'

Apple App Store vetting efficiency

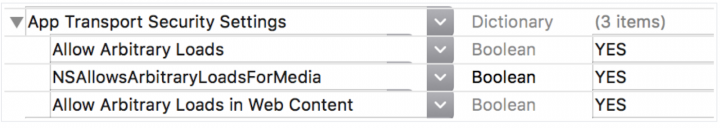

Apple introduced a network security feature, App Transport Security (ATS), with the release of iOS 9.0. By default, ATS checks insecure connections where the lock is broken, printing the denied connections in the console, largely hidden from most users, as viewing the console requires developer tools and setup to view.

What many users don’t know is that Apple allows app developers to disable this security feature entirely, thereby breaking the lock. App developers have the option of disabling ATS restrictions for all, or some, servers, or specific types of data content. This may trigger additional App Store vetting, and the vetting process will determine if the app developer’s reasoning is justified. App users are largely unaware of this process and the fact that once the app developer is allowed to use insecure channels, they can add any data they choose, including private, to the data being sent.

It came as no surprise that apps transferring data insecurely also had ATS disabled by the developer:

- 94% of the apps set "Allow Arbitrary Loads" to "YES", disabling ATS restrictions for all network connections

- 2% of the apps set "Allow Arbitrary Loads" to "YES", disabling ATS restrictions for all media or web content

- 4% of the apps specified the servers in the ATS exception list for disabling ATS restrictions

ATS is effective, if it's enabled. When it isn't enabled, as we have shown, your private data and sensitive information is at risk.

Google Play

Android enforces transport layer security with a feature similar to Apple’s, named "Network Security Config''. App developers specify the policies in the application manifest file. More information on this can be found here.

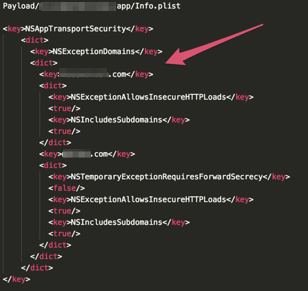

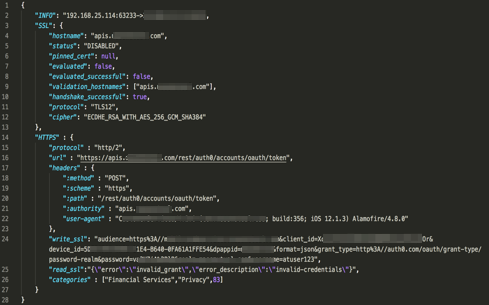

Case study - Financial app

A large financial service’s iOS app was found to be breaking the lock, and worse, this was occurring when the user was logging into the service with their credentials. We sent disclosures to the service and the issue was fixed in subsequent versions of the app.

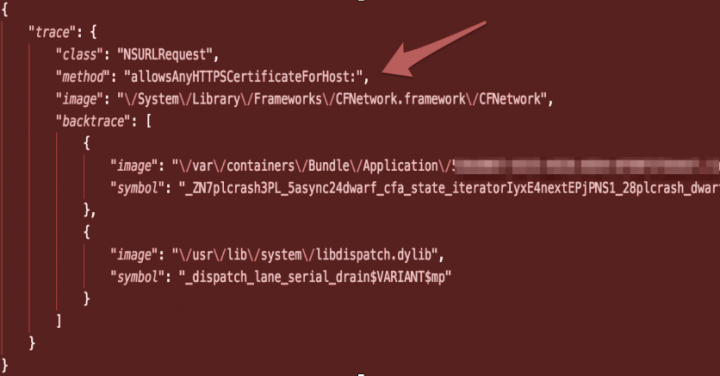

As expected, ATS was disabled for the insecure SSL login server. Interestingly, and something we often see, the class and method names written by the developer signposted the obvious breaking of the lock. In this case, the method was named "allowsAnyHTTPSCertificateForHost".

How best to avoid "breaking the lock" as an app developer

The onus is on app developers to address this issue. Unfortunately, if developers are intentionally choosing to break the lock, in most cases, there is nothing that can be done. However, for the more conscientious developers, the following best practices can help to keep those locks firmly in place.

Developers should avoid using the SSL socket directly to avoid the pitfalls of using secure network protocols. If this is unavoidable, follow security best practices and make sure you avoid common pitfalls, such as empty trust managers, that break the lock and potentially expose the data sent from your app. Google publishes a helpful page of best practices and guidance on this topic.

Developers can also rely on tools to confirm their apps are safe against known TLS/SSL vulnerabilities and misconfigurations as part of their application Software Development Life Cycle (SLDC).

Developers should strongly consider hiring an app security expert to validate and verify that data is protected. This is especially important in cases where developers do follow security best practices only to have resources outside their control – often from Dev-Ops and IT – fail to protect their users' data.

For enterprises, Symantec Endpoint Security (SES) protects corporate mobile devices from exploitation of vulnerabilities occurring as a result of app developer oversights. Enterprises should look to implement Mobile Threat Defense to ensure their devices are protected. Symantec offers Mobile Threat Defense as an integral part of SES. SES can detect issues within the app itself – for example, private data sent insecurely – as well as protect mobile devices from other network, operating system, and app-level threats.

We encourage you to share your thoughts on your favorite social platform.