Daxin Backdoor: In-Depth Analysis, Part One

In the first of a two-part series of blogs, we will delve deeper into Daxin, examining the driver initialization, networking, key exchange, and backdoor functionality of the malware.

Following on from our earlier blog detailing the discovery of Backdoor.Daxin, Symantec’s Threat Hunter Team, part of Broadcom Software, would like to provide further technical details on this threat.

Used by a China-linked espionage group, Daxin exhibits technical sophistication previously unseen by such actors. In particular, it implements communications features that appear to have been designed for deep penetration of highly-secured networks. The focus of this blog series is to document how these features were implemented.

Daxin comes in the form of a Windows kernel driver. In this blog, we will detail the driver initialization, networking, key exchange, and backdoor functionality. In our next blog, the second of two, we will examine the communications and network features of the malware.

Our analysis is based on a Backdoor.Daxin sample (SHA256: ea3d773438c04274545d26cc19a33f9f1dbbff2a518e4302addc1279f9950cef). The forensic evidence collected by us indicates that this sample had been deployed in November 2021 against two separate organizations.

The described Daxin features are contained in many earlier Daxin variants unless stated otherwise. The recent changes to the driver codebase are to support more recent Windows versions and fix certain bugs.

Driver initialization

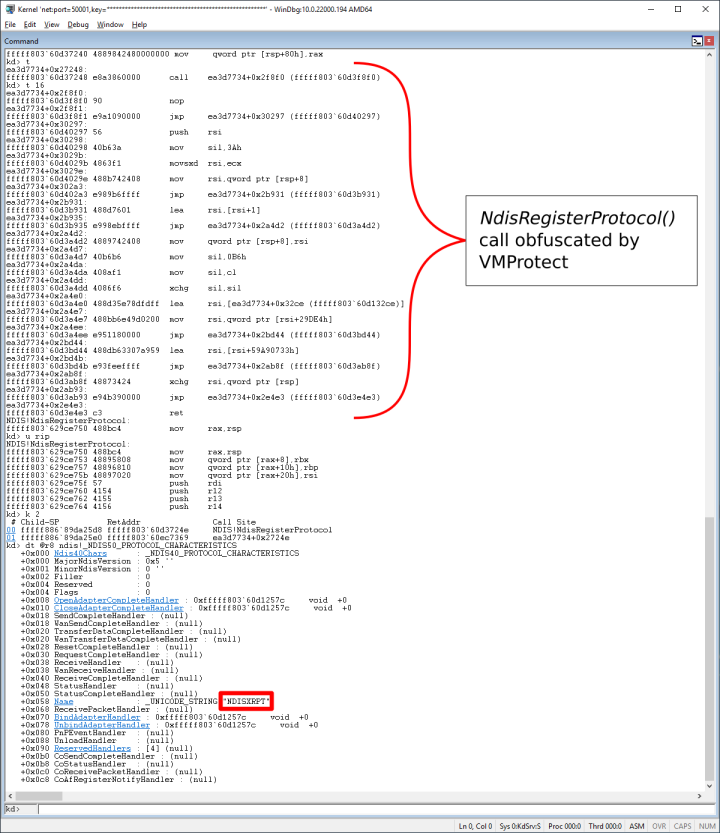

The Daxin sample analyzed appears to be packed with a standard VMProtect packer. Many earlier samples feature an additional, outside, packing layer on top of VMProtect. That outside packer was custom-made for the driver and even reused the same customized encryption algorithm used in the final payload. We believe that the attackers decided to remove that custom packer due to compatibility issues with recent Windows releases.

Whenever the driver is started, the code added by the packer decrypts and decompresses the final payload, and then passes control to the entry point of the decompressed payload. At this point, the malicious code is visible in kernel memory, albeit with some obfuscations.

The bulk of the payload initialization code is involved with the network stack of the Windows kernel. This includes identification of some non-exported structures and hooking of the Windows TCP/IP stack.

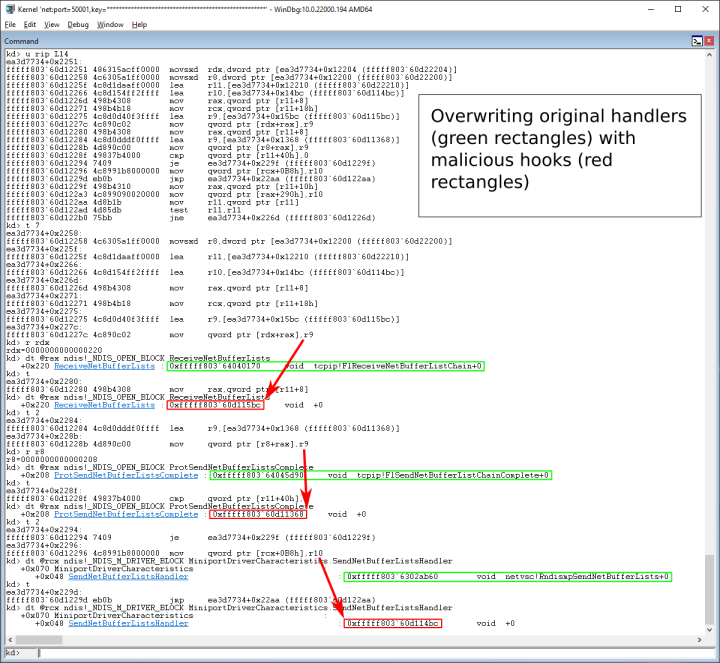

Daxin hooks the Network Driver Interface Specification (NDIS) layer by modifying every pre-existing NDIS_OPEN_BLOCK for the TCP/IP protocol, where the ReceiveNetBufferLists and ProtSendNetBufferListsComplete handlers are replaced with its own. For each of these NDIS_OPEN_BLOCKs, the related NDIS_M_DRIVER_BLOCK may also be modified by replacing any existing SendNetBufferListsHandler. When the SendNetBufferListsHandler is not present, the corresponding NDIS_MINIPORT_BLOCK is modified by replacing NextSendNetBufferListsHandler.

To identify all NDIS_OPEN_BLOCKs for the TCP/IP protocol, the driver relies on calling NdisRegisterProtocol() to create and return a new head of non-exported ndisProtocolList. Then it walks ndisProtocolList of every NDIS_PROTOCOL_BLOCK comparing the Name attribute of each visited NDIS_PROTOCOL_BLOCK structure with the string “TCPIP”. The OpenQueue field of the matching structure points to the list of NDIS_OPEN_BLOCKs to hook. This basic technique is known and documented, but Daxin hooks a slightly different set of handlers. We believe that these adjustments are not exclusive to Daxin and are driven by architectural changes in Windows Network Architecture.

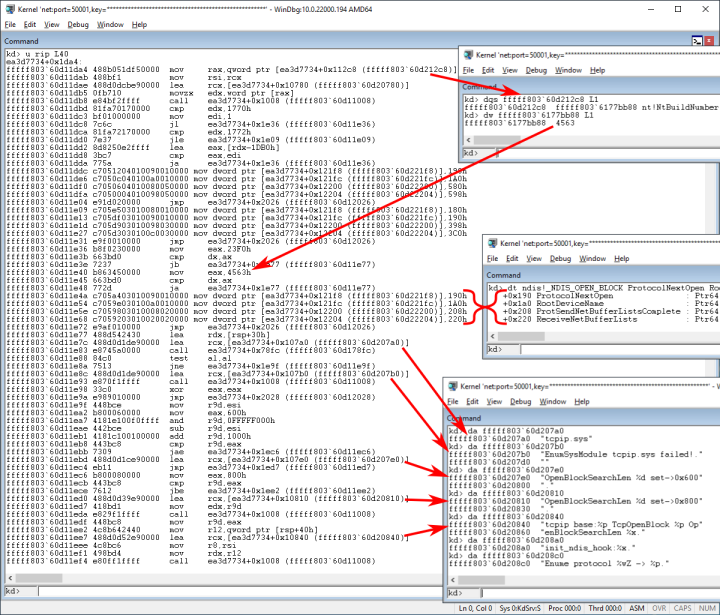

In order to identify the related NDIS_M_DRIVER_BLOCKs and NDIS_MINIPORT_BLOCKs, the driver analyses “ndis.sys” machine code to locate non-exported ndisFindMiniportOnGlobalList() and ndisMiniDriverList. The relevant NDIS_MINIPORT_BLOCKs are then obtained starting with the previously identified NDIS_OPEN_BLOCKs, where the RootDeviceName of each instance is passed as a parameter for the ndisFindMiniportOnGlobalList() call that returns the structure to hook. Finally, to locate related NDIS_M_DRIVER_BLOCKs, the driver walks ndisMiniDriverList checking the MiniportQueue list of each item for the already identified NDIS_MINIPORT_BLOCKs.

Details of the hooking process demonstrated in this blog were captured in the lab using a virtual machine with a kernel debugger attached.

When registering the fake protocol, Daxin calls the NdisRegisterProtocol() API passing a ProtocolCharacteristics argument with the hardcoded Name attribute “NDISXRPT”.

Because the layout of the NDIS_OPEN_BLOCK structure changes between different Windows builds, Daxin needs to determine the correct offsets to use. First it checks NtBuildNumber against a set of hardcoded values for which NDIS_OPEN_BLOCK offsets are explicitly given (Figure 2).

The most recent Windows build number hardcoded in Daxin’s codebase is 17763. It corresponds to Windows Server 2019 and Windows 10 version 1809 (Redstone 5). When the Windows build is not recognized, Daxin attempts to use an alternative method to determine the NDIS_OPEN_BLOCK offsets.

Daxin then collects details of all NDIS structures to hook, as discussed earlier, along with information about the related network interfaces. Finally, for each network interface, it replaces the original handlers with its own.

Networking

Both the ReceiveNetBufferLists hook and the SendNetBufferListsHandler (or NextSendNetBufferListsHandler) hook implement logic to inspect the network packets and then hijack some packets before passing the remaining packets to the original handlers. The ProtSendNetBufferListsComplete hook completes any send operation initiated by Daxin, such that NET_BUFFER_LIST structures owned by malware are removed and deallocated before calling the original handler.

Before describing the hooks’ implementation in detail, we will first examine a few examples of the observed behavior in Daxin.

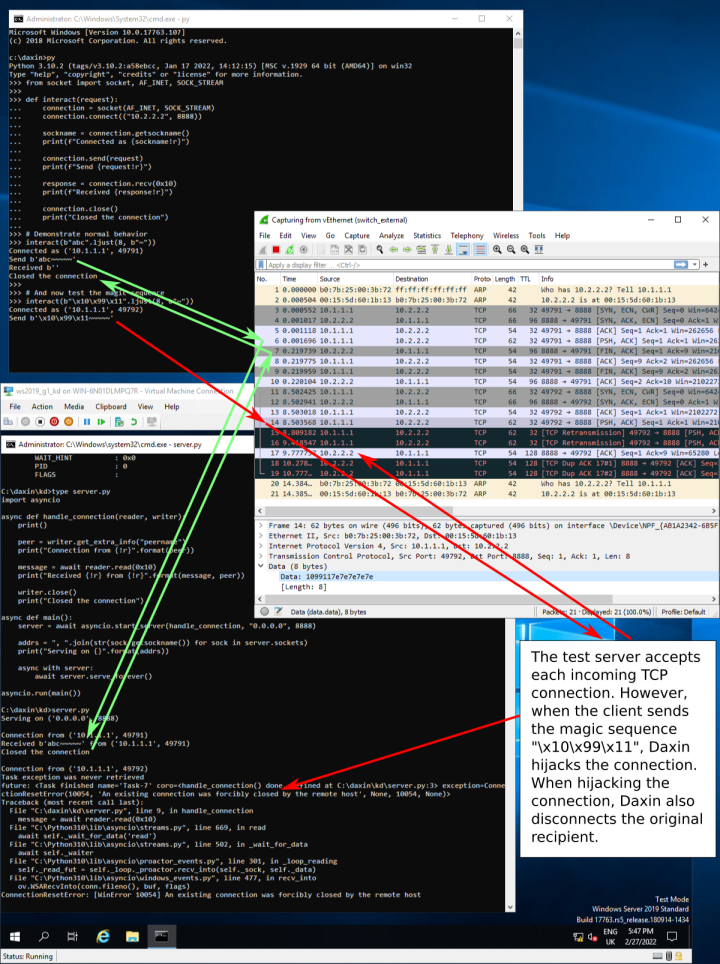

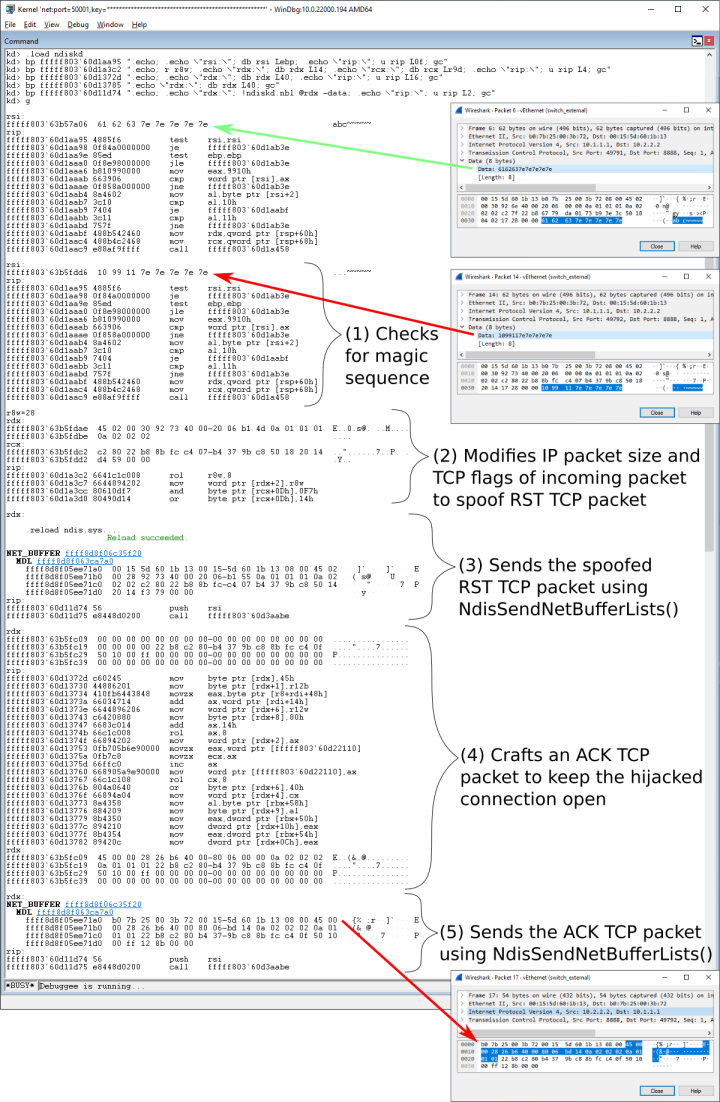

In the first scenario, the ReceiveNetBufferLists hook checks the data section of certain TCP packets for predefined patterns. Any matching TCP packets are then removed from the NetBufferLists before calling the original ReceiveNetBufferLists handler. At the same time, for each removed TCP packet, the malicious driver sends two new packets. The first packet is a spoofed RST TCP packet sent to the original destination, so that its recipient marks the TCP connection as closed. The second packet is an ACK TCP packet sent to the original source. From that point, the malicious driver maintains the TCP connection with the original source, relying on the ReceiveNetBufferLists hook to hijack any related network packets. A test demonstrating this scenario is illustrated in Figure 4.

When generating its network traffic, Daxin uses its own code to forge network packets, bypassing the legitimate Windows TCP/IP stack. To illustrate this, we reconfigured the Windows TCP/IP stack to use non-standard Time to Live (TTL). Since Daxin does not respect the updated parameter, its traffic stands out in the Wireshark capture shown in Figure 4.

The TCP retransmissions in the Wireshark capture are due to our scripts for the kernel debugger that slow down driver response. The retransmissions are not expected otherwise. We decided to activate these scripts to illustrate the internal working of the driver, where we can recognize individual packets from our Wireshark capture, as illustrated in Figure 5.

In another scenario, Daxin initiates a new TCP connection and maintains it over the whole lifetime of the TCP session. The malware relies on the ReceiveNetBufferLists hook to hijack any network packets related to this connection. The hijacked packets do not reach the legitimate Windows TCP/IP driver. An example TCP connection initiated by the malicious driver will be discussed later in this blog series.

In the last scenario, Daxin sends a DNS request using the UDP protocol. The response UDP packet is hijacked by the ReceiveNetBufferLists hook and the DNS response is parsed by the malicious driver. We exercised this functionality in our lab when exploring configuration options related to command-and-control connectivity.

The described scenarios indicate that Daxin implements its own TCP/IP stack. This was confirmed with further reverse engineering of the driver, where we identified both data structures and subroutines implementing IPv4, TCP, and UDP.

The main purpose of the NDIS hooks installed by Daxin is to allow for its malicious TCP/IP stack to coexist with the legitimate Windows TCP/IP stack on the same machine. When certain conditions are met, the hooks also allow it to hijack pre-existing TCP connections.

The ReceiveNetBufferLists hook checks the NblFlags member of the NET_BUFFER_LIST structure at the head of its NetBufferLists argument for the NDIS_NBL_FLAGS_IS_LOOPBACK_PACKET flag. Whenever the flag is set, the hook simply passes the network data to the original ReceiveNetBufferLists handler with no other processing. Otherwise, it calls a helper subroutine passing the NetBufferLists linked list of NET_BUFFER_LISTs. The helper subroutine divides the original linked list of NET_BUFFER_LISTs into two chains: one chain of allowed packets for further processing by the legitimate stack and another chain of hijacked packets to drop. The hook then passes the chain of allowed packets to the original ReceiveNetBufferLists handler. Next, if the NDIS_RECEIVE_FLAGS_RESOURCES flag is not set in its ReceiveFlags argument, the hook releases ownership of the chain of hijacked packets using NdisReturnNetBufferLists().

The SendNetBufferListsHandler hook checks if the NdisPoolHandle member of the NET_BUFFER_LIST structure, passed as its NetBufferList argument, corresponds to the pool created by Daxin itself to use when sending malicious traffic. If so, the hook simply passes the network data to the original SendNetBufferListsHandler with no other processing. Otherwise, it calls the same helper subroutine as used by the ReceiveNetBufferLists hook to divide its NetBufferList argument into two chains. It then passes the chain of allowed packets to the original SendNetBufferListsHandler. Finally, the chain of hijacked packets is retired using the NdisMSendNetBufferListsComplete() or ProtSendNetBufferListsComplete handler.

The helper subroutine used by both hooks walks the original linked list of NET_BUFFER_LISTs extracting network packets from each visited NET_BUFFER_LIST structure and calling the malicious packet filter for each extracted packet. The verdict returned by the packet filter for the first packet from the visited NET_BUFFER_LIST structure determines if the structure should be allowed for further processing by the legitimate stack or dropped by the hook.

The packet filter is central to the networking capabilities of Daxin as it controls dispatching of the extracted packets to various Daxin's sub-modules, where each sub-module implements different functionality. The filter returns an “accept” or “drop” verdict to indicate if relevant packets should reach the legitimate TCP/IP stack or not. It operates as follows:

- Checks if the packet is related to any of the network flows from the malicious network tunnel. If so, it captures the packet for forwarding to the remote attacker via an encrypted channel and returns with a “drop” verdict.

- Checks if the Ethernet source and destination MAC addresses are equal. If so, it returns with an “accept” verdict.

- In cases where it was called from the ReceiveNetBufferLists hook, it checks if the Ethernet source MAC address corresponds to any of the network interfaces of the local machine. If so, it returns with an “accept” verdict.

- In cases of TCP over IPv4 packets, it tracks certain parameters of an active TCP connection for use by TCP hijacking logic in the future (if needed).

- In cases of non-IPv4 packets or when called from the ReceiveNetBufferLists hook, it calls each handler from the list of Daxin’s packet handlers, stopping on the first handler that claims ownership of the packet. Whenever Daxin’s handler claims ownership on the IPv4 packet, the filter returns with a “drop” verdict.

- These Daxin packet handlers are dynamically registered and unregistered by the malicious TCP/IP stack as required, minimizing the overhead. Furthermore, in case of TCP, the list of handlers is bucketed by the server port (which supports TCP servers listening for new connections) or the combination of client and server ports (which supports TCP sessions). The packet is parsed before calling handlers and the parser logic limits the combination of supported protocols to ARP, UDP over IPv4, and TCP over IPv4.

- In cases of TCP over IPv4 packets when called from the ReceiveNetBufferLists hook, it checks that the TCP data in the packet:

- Starts with the string “POST” and contains the string “756981520337” without any line break “\r\n” in-between, or

- Starts with the sequence of bytes 0x10 0x99 0x10 and is at least eight-bytes long, or

- Starts with the sequence of bytes 0x10 0x99 0x11 and is at least eight-bytes long

- When a match is found, it triggers hijacking of the related TCP connection and returns with a “drop” verdict. It should be noted that these checks are not limited to the start of the TCP conversation, and so it is possible to trigger hijacking after exchanging an arbitrary amount of data. This provides the option to start communication with the malicious driver at the end of a long conversation with a legitimate server hosted on the infected computer.

Finally, the ProtSendNetBufferListsComplete hook walks the list of NET_BUFFER_LIST structures passed as its second argument checking if the NdisPoolHandle member of the visited NET_BUFFER_LIST structure corresponds to the pool created by the malicious driver itself to use when sending malicious traffic. The matching structures are removed from the list and, after validating the Flags member, deallocated. The hook then passes the modified list to the original ProtSendNetBufferListsComplete handler.

A technical paper by Kaspersky on the Slingshot advanced persistent threat (APT) group describes a technique to identify NET_BUFFER_LIST that is very similar to how the ProtSendNetBufferListsComplete hook works, including the use of NdisAllocateNetBufferListPool() and NdisAllocateNetBufferAndNetBufferList(). However, there are no other significant structural overlaps.

Key exchange

Whenever Daxin hijacks a TCP connection, it checks the received data for a specific message. The expected message initiates a custom key exchange, where two peers follow complementary steps. When discussing this key exchange protocol, we are going to use the term “initiator” when referring to the side sending the initial message. The opposite side will be called “target”. Interestingly, the analyzed sample can implement both the initiator side and the target side of this custom key exchange protocol.

Firstly, Daxin starts the target-side protocol for each hijacked TCP connection. Additionally, it can be configured to connect to a remote TCP server, where it exchanges a certain handshake and then also starts the target-side protocol. This scenario will be discussed in our next blog in this series in a section titled “External communication.” Finally, Daxin can be instructed to connect to a remote TCP server, where it starts the initiator-side protocol. We will expand on this in the next section.

Backdoor capabilities

A successful key exchange opens an encrypted communication channel. Daxin uses this communication channel to exchange various messages. Some messages instruct the malware to perform various operations, such as starting an arbitrary process on the affected computer. Others carry results of these operations, such as output generated by the started process, for example. The set of operations recognized by Daxin is rather compact, with the most basic operations being reading and writing arbitrary files.

Daxin can also execute arbitrary EXE and DLL binaries. In the case of EXE files, Daxin starts a new user-mode process. The standard input and output of the started process is redirected, so that the remote attacker can interactively send input and receive output. When ordered to execute a DLL file, Daxin performs injection into one of the pre-existing “svchost.exe” processes.

Daxin provides a dedicated communication mechanism for any additional components deployed by the attacker on the affected computer. Any compatible component can open a “\\.\Tcp4” device created by Daxin to register itself for communication, where it can optionally assign a 32-bit service identifier to distinguish itself from other services that may be active on the same computer. Daxin then forwards any matching communication between the remote attacker and registered services.

Next, the remote attacker can inspect and update the backdoor configuration. The configuration is implemented as a generic key-value structure that is stored in an encrypted form in the Windows Registry for persistence. All used configuration items will be listed in the “External communication” section in a subsequent blog.

There are also dedicated messages that encapsulate raw network packets to be transmitted via a local network adapter. Any response packets are then captured by the malicious driver and forwarded to the remote attacker. This allows the remote attacker to establish communications with any servers reachable from the affected machine on the target’s network, creating a network tunnel for the remote attacker to interact with servers of interest.

Finally, a special message can be used to set up new connectivity across multiple malicious nodes, where the list of nodes is included in a single command. For each node, the message provides the details required to establish communication, specifically the node IP address, its TCP port number, and the credentials to use during custom key exchange. When Daxin receives this message, it picks the next node from the list. Then it uses its malicious TCP/IP stack to connect to the TCP server listed in the picked entry. Once connected, Daxin starts the initiator-side protocol. On the peer computer, if it is infected with a copy of Daxin, the initiator traffic causes the TCP connection to be hijacked, as explained earlier. This is followed by the custom key exchange to open a new encrypted communication channel. Next, the connecting driver sends an updated copy of the original message over this new channel, where the position of the next node to use is incremented. The process then repeats for the remaining nodes on the list.

The TCP connections created during the above process, along with the connection that received the original connectivity setup instruction are then used for subsequent communications. Whenever an intermediate node receives a message, it may execute the requested operation or forward it along the connectivity path. For certain operations, the node to execute the operation is specified by the position along the path. In some remaining cases, the operation is always forwarded to the last node. Finally, certain operations are always executed by the first node only.

This method to create multi-hop connectivity is noteworthy. It is not uncommon for the attackers to jump through multiple hops in victim networks to get around firewalls or to better blend in with usual network traffic. This usually involves multiple steps when using other malware, where each jump requires a separate action. However, in the case of the analyzed sample, the attackers combined these into a single operation. This may indicate that Daxin is optimized for attacks against well-protected networks and cases when the attackers need to periodically reconnect into the compromised network.

The ability to use hijacked TCP connections for backdoor communications is also significant. This may be required when exploiting tightly controlled networks, with strict firewall rules or when the defenders monitor for network anomalies. On the infected machine, any malicious network connections are bypassing the Windows TCP/IP stack, and this could provide some degree of stealth. The attackers invested significant effort in implementing these features with a malicious TCP/IP stack supporting TCP connection hijacking.

The implementation of network tunneling, where the malicious driver passes the packets directly between the remote attacker and the target’s network demonstrates how the attackers attempt to minimize their footprint without sacrificing functionality.

Backdoor demonstration

In order to demonstrate Daxin’s backdoor capabilities, we prepared a lab setup to both illustrate what was described in the previous section and also to collect some examples of malicious network traffic to discuss later.

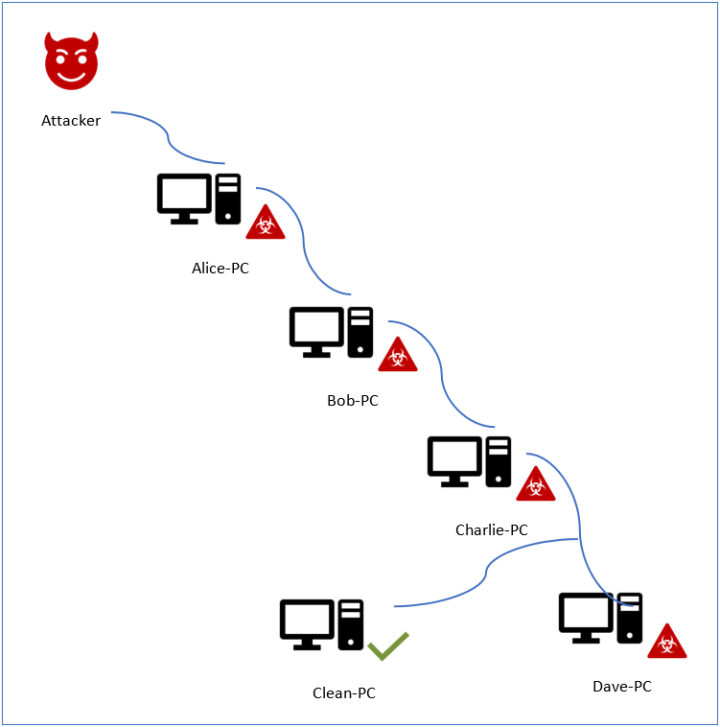

Our lab setup consisted of four separate networks and five machines. Some of the machines had two network interfaces to communicate with different networks, but all packet forwarding functionality was disabled. Each machine ran various network services that were reachable from its neighbors only.

In our setup, the attackers can communicate with “Alice-PC”, while all of the other machines are unreachable directly to the attackers. This simulates the network of a hypothetical victim, where machines serving different roles have very restrictive connectivity. “Alice-PC” could represent a DMZ service that is accessible from the internet, but all the other machines are tightly isolated.

We infected all of the configured machines with Daxin, except for just one machine deep in our network that was left clean. Next, based on our understanding of the malicious communications protocol gained during reverse engineering of the malicious driver, we implemented a rough client to interact with the Daxin backdoor running on “Alice-PC”. We used this client to instruct the backdoor on “Alice-PC” to create a communications channel to “Dave-PC” passing via two intermediate nodes: “Bob-PC” and “Charlie-PC”. The connectivity was established successfully, and we were able to interact with all the infected machines. Finally, we were able to use this malicious network tunnel via “Dave-PC” to communicate with legitimate services on “Clean-PC”.

Conclusion

This concludes the first part of our technical analysis of Daxin. In our second, and final blog, we will examine the communications and networking features of the malware.

We encourage you to share your thoughts on your favorite social platform.